Since making his inauspicious debut on South Broad Street in

2007 with the pink-hued, milk-bottle-shaped Symphony House, developer Carl

Dranoff has gone on to do something that once seemed improbable: He has

resurrected a big stretch of the battered commercial street as a residential

boulevard.

A canny developer, Dranoff seems to possess a sixth sense

about where the real estate market will go next. He gets his urbanism mostly

right, by packing the ground floors with generous commercial spaces and finding

tenants to turn the lights on. But architecturally, his growing collection of

condos and apartment houses has been a mixed bag.

His follow-up to Symphony House, a mid-rise called 777,

drips with Art Deco-inspired bling, while his latest, Southstar Lofts, is

shaping up to be a rather staid white box. It's as if his South Broad is still

trying to figure out what it wants to be when it grows up. Grand boulevard?

Generic apartment row?

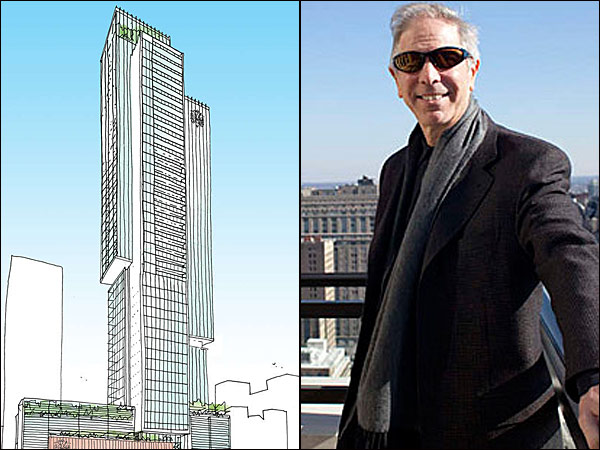

Now Dranoff is back with a fourth project near Spruce Street

and it strikes a pleasingly different note. At 567 feet, it will be the tallest

high-rise built just for residential use in the city. Although it's been

clunkily named SLS International, the beanpole of a tower is the most

sophisticated design Dranoff has ever commissioned.

If you want proof that architecture follows the money, here

it is. Unlike Dranoff's earlier projects, which were on the southern, untested

fringe of downtown, it occupies one of Center City's most glittering

crossroads, across from the Kimmel Center and steps from the Wilma Theater. The

official budget is $200 million.

Dranoff is clearly out to fashion South Broad into a

desirable address and recognizes that pink concrete won't cut it anymore. So

instead of the usual suspects and the usual designs, he sought out a top New

York architecture firm, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates, which has built

skyscrapers around the world.

Known for producing refined buildings with strong, legible

shapes - such as Chicago's 333 Wacker Drive and Shanghai's World Financial

Center, the tallest building in China - the firm also has left its mark on

Philadelphia. The quality here runs the gamut, from the stately Logan Square

office-and-hotel complex, to the more ponderous BNY Mellon Bank Center on

Market Street, to the airy cube of Children's Hospital's main pavilion.

From indications so far, the long-limbed, 47-story SLS tower

promises to be in the refined and elegant group. Like Logan Square, it's a

luxury hybrid, combining a 149-room boutique hotel and 125 condos. But instead

of separate elements, KPF stacked the pieces vertically, with 28 floors of

condos on top of the hotel. Combining two uses into one is what enabled Dranoff

to build a tower that hovers above the competition.

KPF follows the current fashion and dresses the exterior in

glass, but it's more than a simplistic, straight-up pile of floors.

KPF envisioned the tower as a composition of interlocking

boxes. It's a visual trick, achieved by cantilevering the north and south walls

out from the central shaft in asymmetrical sections. They jut out only about

five feet, but it's enough to provide a sense of depth and scale that you don't

get with slick glass walls.

KPF's puzzle box doesn't just sit statically on its podium;

it appears to slide over it, like a flash drive plugging into its USB port. The

podium, which will house a parking garage and hotel meeting rooms, also gives

the impression that it's made of interconnected boxes. Scrims of dark terra

cotta will pop out from the glass to screen the parking decks.

It's true there is a whiff of the corporate in the design.

The immense hotel insignia that is shown plastered on the podium and near the

crown certainly doesn't help. (Is there a brand consultant in the house?) But

there is still time for the architecture to settle down into something a bit

more homey. As we learned at Symphony House, which was originally depicted in a

buff limestone color, material choices will be crucial.

If it's anything like the rendering, SLS will be far better

than any of the city's new high-rises. Dranoff and KPF deserve props for

positioning the tower a respectful distance from both Spruce Street's Center

City One condos and the lacy Gothic facade of the Broad Street Ministry, housed

in the former Chambers-Wylie Memorial Presbyterian Church. The advantage of

thin towers is that they don't completely block out the sun or views.

It helps that SLS is lean as well as tall. The tower floors

will be just 7,500 square feet, making it as leggy as a fashion model. Just a

decade ago, Philadelphia condos were far bulkier. The St. James' floor plates

are 16,800 square feet, the Murano's 11,200. For all that height, SLS has fewer

units than 10 Rittenhouse.

But packing in the same number of units requires more

floors. Philadelphia's residential high-rises have been gaining an average of

100 feet in every building cycle - going from 300-footers in the 1980s, to

400-footers in the early 2000s.

Now that we're into the 500-foot range, it's likely that

Philadelphia condos will continue to get taller, as they have in New York,

where a forest of super-tall, 1,000-foot-plus buildings is rising near Central

Park. The demographic for the super-tall condos tends to be older, and they

want a full menu of concierge services. The hotel-condo combo makes that easier

to provide.

But the mix also makes things more complicated on the

ground. To serve the building, Dranoff is seeking zoning changes from City

Council to allow big driveways on both Broad and Spruce Streets, as well as a

height increase. Because the building's loading dock is planned for narrow

Spruce Street, delivery trucks will have to back in, a maneuver sure to cause

traffic headaches. The first Council hearing is scheduled for Feb. 12.

Like other hotel developers, Dranoff is seeking a state

subsidy - $10 million - as well as the city's usual 10-year property-tax

abatement. That's a lot of public subsidy for a building that will serve the

one percent.

But at least the rest of us will get to enjoy looking at it.

Source: Philly.com

No comments:

Post a Comment